This is a draft for the book chapter

Psychology of the Critters

1 Introduction

The primary purpose of this chapter is to describe how a critter in our model decides how to behave. As I write I learn that my description of “deciding how to behave” necessarily includes a description of physical attributes of the critter and its world. A critter makes decisions because of physical facts concerning its body and its world. Furthermore I discover that my description of physical attributes, in this introductory level of the model, requires most of the writing in this chapter. A critter has senses, memories, calculating abilities, and ambitions to continue living and reproduce. For all of these we need a description.

1.1 The tension in this model between simplicity and completeness.

We want our model of a critter to be simple so we can easily comprehend behavior produced by the model. But we also want our model to echo aspects of our experience as humans, and this adds complexity and tension.

So I separate and clarify the description under this outline:

- In heading 2, I will describe the critter’s operating cycle.

- Under heading 3, I will describe the attributes needed by a critter in the initial condition in the model. In that condition critters survive at the lowest possible level as hunter-gatherers.

- Heading 4 will present features necessary to allow the advancement in critter prosperity shown on the tabletop with a resource pattern.

- Finally, under heading 5, I will list a few features that we will need as we extend the model to ever more humanistic situations.

1.2 Greater reality decides whether a critter succeeds in its chosen acts.

There is a way in which we need to remember that a critter has limited control. A critter will not necessarily succeed in completing an act which it has chosen. Some physical reality not anticipated in the critter’s calculation may limit the extent to which an attempt succeeds. This limitation is reminiscent of our human experience, of course.

Sometimes I write about a critter "deciding to act" without adding the notice that success is not guaranteed for the critters attempt to act.

2 The Critter’s Cycle

We model the critter’s psychology as an infinite loop, a cycle which repeats itself as long as the critter lives. I sometimes refer to one of these cycles as a “moment” in the critter’s life.

Here is a list of the major processes that occur in the critter during each cycle:

- Sense the external environment (with whatever senses we give the critter).

- Sense internal conditions. These conditions include the amount of water and sugar in storage and thus whether the critter is motivated by thirst or hunger.

- Search memory for prior experiences which are relevant to the current situation.

- Calculate or “think”, considering all data gathered from senses and memory. Reach a decision about what act should be attempted at this time.

- Attempt the act.

We modelers, who are making these critters, remember that the above processes in the critter occur because they are driven by an enclosing process which is under our control, but not under the control of the critter. The cycles repeat for a length of time which is determined by our enclosing process, since we have not empowered the critter to commit suicide. It is the enclosing process, for instance, that declares the critter dead if the critter’s store of a resource falls to zero.

3 The Critter’s Attributes in the Initial Condition

In this section we consider the attributes of critters in the

initial condition.

3.1 Body

The critter has a body which consumes water and sugar in every moment of its life. The critter’s body can carry a supply of each of these vital resources, so that a critter only occasionally needs to imbibe more.

3.2 Goals

The critter has goals. The reader should remember that a critter has not chosen to have goals. It has its life and goals because we have made it that way.

The principal goal is to keep on living and this translates into a goal to find water and sugar. Even if the critter has adequate stores of water and sugar for the immediate future, it still has the goal of finding more of each.

An additional goal is to reproduce.

3.3 Senses

3.3.1 External Senses

A critter has a sense area around its body in all directions. This area extends outward from the critter’s body a distance analogous to an arm’s length. A critter can sense any object that falls partly or entirely within its sense area but cannot sense anything outside its sense area. When a critter senses an object it also senses the object’s type, i.e. a drop of water, a crumb of sugar, or another critter.

A critter can sense where it is on the plane which is its world. It knows its location in terms of X and Y. A critter also has a sense of direction. In our model this is expressed as an angle in the X,Y plane. Whenever a critter senses another object in its sense area it senses the direction from itself to the object.

3.3.2 Internal Senses

A critter can sense the level of its internal stores of both water and sugar. In particular, there is a short-supply threshold which a critter can sense. If the level is below this threshold then the critter is thirsty (if for water) or hungry (if for sugar). Otherwise the critter senses the supplies to be adequate.

3.4 Actions Available

The critter has actions which it can perform.

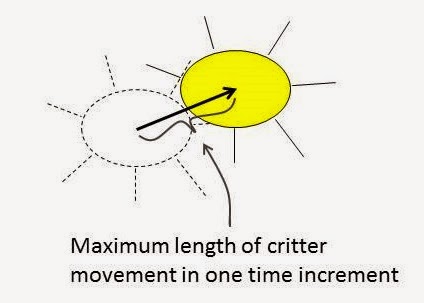

3.4.1 Move

The critter can move in any direction which it chooses. The length of the move is a predetermined step size, a length probably about equal to the diameter of the critter’s body. But if the critter collides with another object when it attempts to move, then the actual length of the move accomplished will probably be shorter.

3.4.2 Imbibe Resource

The critter can imbibe a resource which lies at least partially in its sense area.

The amount that it can imbibe in one time increment is limited to some maximum analogous to a meal. This maximum is substantially more than the amount of the resource that the critter’s metabolism consumes during a single time increment, so that we can expect that the amount of time spent imbibing is small compared to the amount of time spent in other activities.

The amount that a critter can imbibe is also limited by the total carrying capacity of the critter for this resource, but probably, modeling humans, this upper bound is reached only after a considerable number of full meals.

3.4.3 Reproduce

A critter can reproduce when it has at least adequate supplies of both essential resources. It reproduces by dividing in two. Each of the offspring gets half of each of the parent’s resources. One of the critters retains the memory accumulated by the parent, the other starts new with an empty memory.

3.5 Memory

The critter remembers every previous instance in which it discovered a resource. For each such instance it remembers whether the resource was water or sugar, the time (the computer cycle number), and the X,Y location. It also remembers whether some of that resource was still there when the critter departed, presuming, of course, it did not consume all that it found.

3.6 Thinking or Calculating Capacity

The critter “thinks” following rules such as these.

- If one of its resources is in short supply, it gives priority to finding and imbibing more of that resource.

- If it can sense a resource, it chooses to imbibe even if that resource is not in short supply.

- If no resource is in short supply, with low probability it might choose to reproduce.

- Otherwise it will choose to move.

When a critter chooses to move it will also choose a direction for its movement. To choose this direction first it will notice which of its resources is in shortest supply. Then, if it is old enough to have useful memory of where it has found this resource before, it will use this memory to choose a location on the plane where it guesses it may find this resource once again. Naturally, in considering its memories, it will give preference to those memories in which there was still some resource on the plane when the critter was last at that location. The critter will move toward that location. But if the critter is too young to have any helpful memories it will choose a direction at random.

4 Additional Attributes with first Resource Pattern

Now we will consider what additional attributes we must give our typical critter when we want a population of its kind to be able to exploit a pattern of resources, as described

here.

The critter will be able to pick up and carry a resource from one location to another. We will call this ability the critter’s “backpack”. The amount that can be carried in the backpack will be more than the amount a critter can imbibe in a single time increment but probably less than the amount the critter can carry in its internal store. We will give the critter ability to pick up the backpack’s capacity, as well as the ability to set it back down, in a single time increment. The critter will be able to sense the type and amount of resource in its backpack, and will be able to imbibe from its backpack.

The critter will be able to carry “rules” in its mind and will be able to recognize circumstances in which a rule applies to its choice of how to act.

5 Additional Attributes for the Fancier Critter to Come

As we try to make the life of critters more like the life of humans — more socially complex, secure, and prosperous — we will see that we have to give additional capacities to each typical critter. We will not go far at this time to list the attributes which will become necessary, but for the sake of looking ahead we name a few attributes which will prove valuable.

- Ability to do nothing in a particular moment, to wait or remain idle.

- Ability to embrace critter-specific rules of behavior, so a population will contain individuals which consistently behave in distinct ways.

- Ability to recognize specific other critters, so other critters can become known as individuals.

- Ability to trade, including ability to offer to exchange one resource for the other resource.

- Ability to signal other critters, comprising ability to display symbols and to recognize symbols displayed by other critters.

- Ability to experiment with symbols, to remember experience with giving and recognizing symbols, and thus ability to spontaneously develop a primitive language.